Constructor Theory – More Digitalia and Relativia in Counting Seconds

Constructor theory’s weakness isn’t that it is wrong, we don’t know that yet. The suspicion is that it is incomplete. It maps what transformations are possible but doesn’t collapse back into predictive, observable laws. A framework that cannot ground itself in testable reality, I would claim, is epistemically malformed, elegant scaffolding without a foundation. Until it connects possibility to empirical consequence, it remains, in my mind, an unfinished sketch rather than a theory.

I’ve always quite liked “Time is what keeps everything from happening at once…” (from Ray Cummings’ short story The Time Professor (1921)).

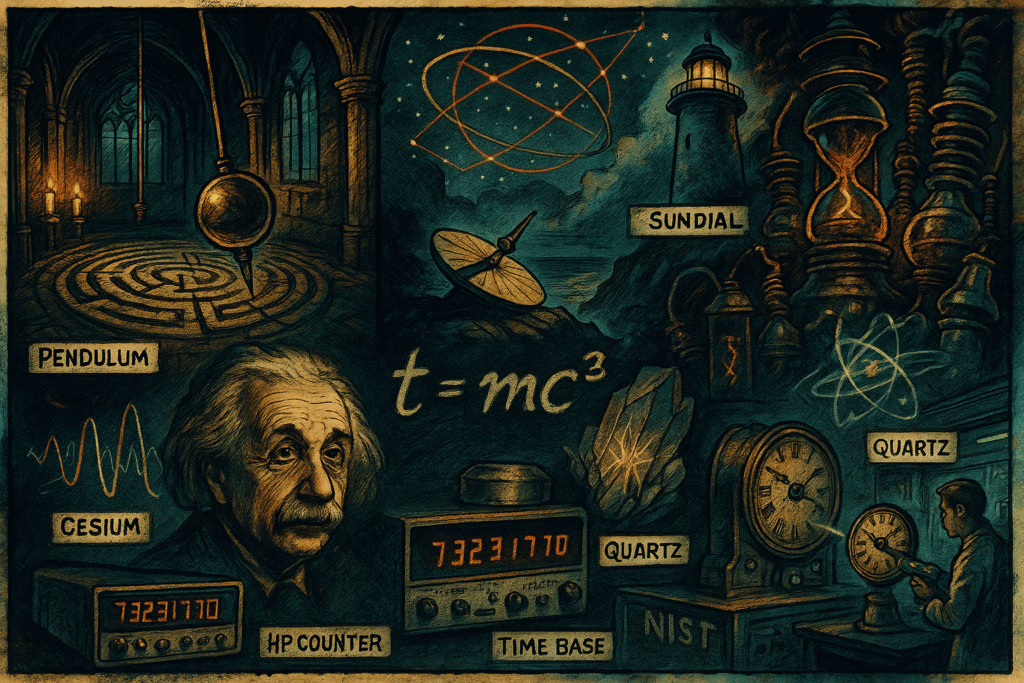

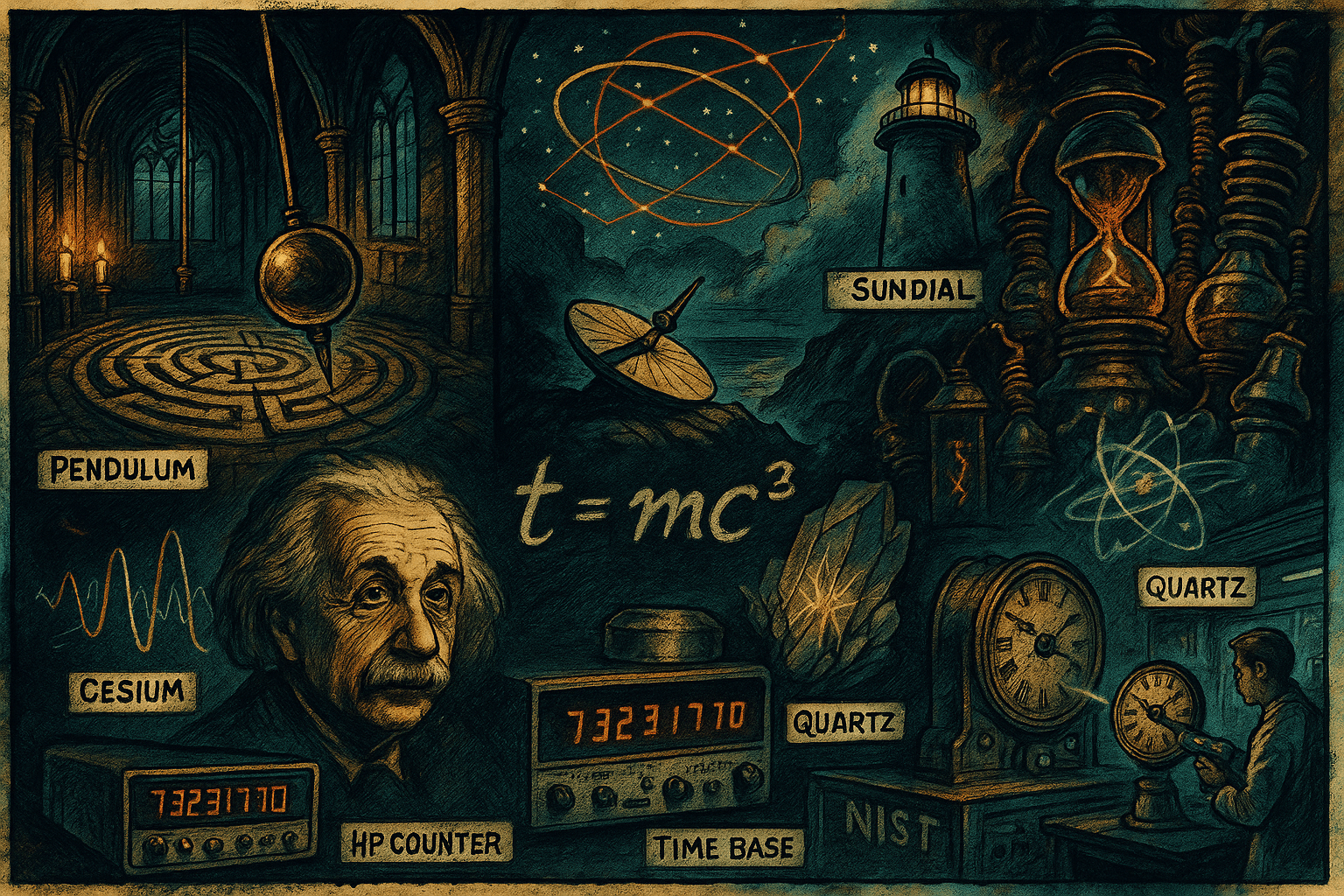

“Fundamentals of Statistical and Thermal Physics” by Fredrick Reif and “Statistical Physics” by George Wannier both conclude with interesting discussions of Noise, Brownian Motion, Fluctuations and Irreversibility. “Noise and Fluctuations” by D.K.C. MacDonald does a deep dive into the topic; the book has a very conversational tone. “Selected Papers on Noise and Stochastic Processes” edited by Nelson Wax contains seminal papers; these are rather meaty. “Investigations on the Theory of Brownian Movement” by Einstein is a great little read. Einstein’s contributions to Physics on the microscopic scale surpass those on the macroscopic scale: Brownian Motion, and the Photoelectric Effect substantiated the atomic theory of matter and discrete interaction between radiation and matter.

While I don’t think Constructor Theory gets it right, the generalized belief by most physicists in ‘time’ as a physical entity is by far one of the biggest roadblocks in the progress of physics. There is simply no logical or physical reason whatsoever to believe that time exists as a physical object, field, matrix, etc. As soon as the community of physics researchers realizes this, the field will begin to make progress again. ‘Time’ is solely a mental conceptual measuring tool that we use to map out and track the relative interactions of physical bodies with each other. The successional interaction of all physical things in the universe with all other physical things is what creates the shape of space, as well as the very complex relative rates of internal and externally interactive motion that we use the measuring device ‘time’ to understand. The milliseconds, seconds, minutes hours, etc, of ‘time’ are no different than the millimeters, centimeters, meters, etc, on a ruler. They are not physically *there* they are just marks on a measuring device.

Here’s the clean way to connect the video’s point (“no absolute time”) with how metrologists define—and are preparing to redefine—the second.

1) Physics: why there’s no universal, absolute time

- Relativity: In Einstein’s framework, “time” is a coordinate you’re free to choose; only proper time (what a specific clock measures along its path) has invariant physical meaning. Different observers—and the same observer at different altitudes or speeds—can have different tick rates. That’s why there is no single, global “now.” (Wikipedia)

- Quantum-gravity tension: In quantum theory, we usually treat time as an external parameter; in general relativity, it’s dynamical and frame-dependent. That mismatch is the “problem of time” the video alludes to. (arXiv, Wikipedia)

2) Deutsch & Marletto’s move: time without “time”

Deutsch and Marletto propose constructor theory: formulate laws as statements about which transformations (“tasks”) are possible in principle, performed by constructors (devices that can act cyclically). Because tasks are defined without referencing a time parameter, they then show how a notion of duration emerges by comparing changes to “null tasks” (turn on/turn off). That’s the paper the video is paraphrasing. It’s deliberately non-reductionist and highly abstract, but it is a concrete technical proposal (not just vibes). (arXiv)

3) Metrology: so who decides how long a second is?

- Today’s second (since 1967; wording refined 2019): We fix the value of the caesium-133 hyperfine transition frequency to 9,192,631,770 Hz and define 1 s as that many periods. That’s a convention agreed internationally (CGPM/BIPM), not something NIST can change on its own. (NIST)

- Realization vs. definition: National labs (NIST, PTB, NPL, etc.) build clocks that realize the definition locally and compare them to build global time scales (TAI/UTC). Relativistic corrections are applied (altitude, velocity), because clocks higher in Earth’s gravity well tick faster. We’ve measured those differences over 33 cm and even 1 mm height separations. (NIST)

Human sanity check: there isn’t a cosmic referee of “one true second.” There’s a democratically agreed definition that any sufficiently careful lab can realize. Your personal second is your proper time; society’s shared second is a convention we maintain with exquisitely stable devices and relativity corrections.

4) “The second can slip and slide”—true in practice, not by decree

- Clocks really do diverge because spacetime isn’t flat and because devices aren’t perfect. That’s physics (time dilation), not metrologists moving the goalposts. (NIST)

- To keep civil time stable, standards bodies are ending leap seconds by/before 2035, decoupling UTC from Earth’s irregular rotation (so computers don’t hiccup every few years). That’s a governance choice about clock coordination, not a change to the length of the second. (Wikipedia, ITU)

5) Is NIST “changing” the second?

What’s actually happening: the community is preparing to redefine the second using optical clocks (strontium, ytterbium, aluminum-ion…) because they’re orders of magnitude more precise than caesium. The aim is continuity—the new definition must match the current second within uncertainties—so your stopwatch won’t suddenly run fast or slow. NIST’s new aluminum-ion clock record (July 2025) is part of meeting those technical criteria; the decision itself will be taken internationally (BIPM/CCTF → CGPM), with a target window around ~2030 once readiness criteria are satisfied. (NIST, optica.org, NIST, bipm.org)

Bottom line (sanity & humanity)

- Physics says there is no absolute, global time; every clock rides its own spacetime path.

- Metrology gives us a shared yardstick by definition and consensus, realized by hardware and corrected by relativity.

- Redefinition to optical clocks won’t “change how long a second is” in everyday life; it just anchors our shared yardstick to a better—more stable, more universal—physical reference while preserving continuity. (NIST, NIST)