I’m a Logic user but over 10 years ago there was a plugin made for CuBase that introduced noise at -384dB (completely inadiable) which reduced CPU overhead from 40% down to 5%.

Good video. As a computer engineer, I just wanted to clarify what subnormal numbers are and how they work. To do that, let’s analyze Single Precision Floats. These have 1 sign bit, 8 exponent bits, and 23 mantissa bits (for a total of 32 bits). As the video explaned, they’re stored in scientific notation. Since computers work in binary though, base 2 scientific notation is used, instead of the regular base 10. This means numbers are represented like this: ± m × 2^e, where m is the mantissa and e is the exponent (and ± depends on the sign bit). Now what’s important is that, since we’re writing it in base 2, m can always be written as 1.[something], adjusting the exponent as needed. For example, 0.5 is stored as 1.0 × 2 ^ (-1), and 5.25 is stored as 1.0101 × 2 ^ (2). (Note that, again, I’m writing m in binary, and 1.0101 in binary is 1.3125 in decimal). Now, since m always starts with 1. , this first bit can be implied to save space for one extra meaningful bit instead. So basically, the first bit holds the sign (1 for negative), the next 8 bits store the exponent (with a bias (which is 127 for single precision), that means a value of 10000000 means the exponent is 1), and the remaining 23 bits are the decimal part of the mantissa (and the 1. is implied). This works well for most numbers, but there’s a problem. Since we have 8 exponent bits, if we ignore subnormal numbers, the smallest possible exponent would be -127, and so the smallest (positive) number you would be able to store is 1.00000… × 2^(-127), and the second smallest number would be 1.00…[22 zeroes]…01 × 2^(-127). Which is just 2^(-150) bigger than the smallest one. Basically, you can store numbers that are just 2^(-150) apart, but you have a gap between 0 and 2^(-127), with no intermediate values. Subnormal numbers were invented to bridge this gap. All numbers that have 00000000 as their exponent (which would be -127) are now interpreted differently. First, the exponent is interpreted as -126, second, the 1. that is usually implied is not implied here. This fills the gap between 2^(-127) and 0 with equally spaced numbers that are 2^(-149) apart. But it created a different problem: FPU circuits are made for regular numbers, and since subnormal numbers use a different encoding, they have to be handled differently. x86 CPUs do that by splitting these operations involving subnormal numbers into multiple steps (using microcode), but this causes slowdowns, which is exactly what the video showed.

6:00 there’s a famous example: 0.1 + 0.2 produces 0.30000000000000004 and not 0.3 – works everywhere: browser javascript, c++, java

And the catch is, that .01+.02 , .1+.1 , .1+.3 , or 1.1+1.2 work just fine. But some combinations of numbers trip up

@lucas_is_away yes in C#. there is an additional number type Decimal that uses base 10, but it is significantly larger, slower, and not the default. 0.1 + 0.2 still isnt equal to 0.3. this is true of every language that uses IEEE 754 floats, no exceptions

its really simple to test this. go ahead and type `0.1 + 0.2 == 0.3` into a lua interpreter. again, there are *no exceptions*. this is how binary floating point arithmetic is specified to work.

I first ran into this issue on early iOS, where subnormal wasn’t enabled and clearing flush-to-zero simply crashed the whole phone. So I had to defend changing our API definitions of max and min float values to be platform dépendant. But a colleague had worked in high-end audio and had come across the same fade-out issue. Their solution was to add a tiny bit of noise which they had always planned to do “eventually” for antialiasing.

The problem with floating point numbers is ever worse than you think! On Intel, the x87 floating point coprocessor/ instruction set perform operations in 80-bit extended precision. At the start, the floats are converted from 32- or 64-bits to 80-bits. After the operations are complete, they are truncated to either 32- or 64-bit precision. This means depending on how the code is written, you can get slightly different results.

As a Hardware Design Engineer who did some work in Control Flows of a Modern FPU this actually is quite suprising. Subnormals in the FPU itself are not significantly more expensive to calculate than normals. On the input side a subnormal just means you set the bias bit to 0. For FP32 that is about 8 OR-gates. Then you don’t care until the output where you count leading zeros to shift the mantissa and change the exponent. Here subnormals just mean you need to clamp the exponent and shift amount, which costs about as much as an 8bit adder IIRC. For our unit none of these could ever cause additional clock cycles to requires in addition, multiplication, casting or comparison. For division depending on precision we could go from 8 to max 12 cycles IIRC. Compared to 27 or so bit wide mantissa additions and multiplications these should be neglible in other units too. So I suspect what is happening is that the 0s generated by rounding subnormals then cause the FPU to not be used anymore after that for some chunks of the data. So it is not really subnormals that are bad, but floating point calc in general?

It seems that for Intel CPUs it stopped being an issue with Sandybridge. I have a 2014 laptop with no subnormal penalty at all. For AMD, in Bulldozer and Piledriver the subnormals were done in microcode, Pentium and early Core style, and that’s where figures of hundreds of extra cycles comes from. Ryzen seems to only take a handful of extra clock cycles, so for fat packed SIMD arrays full of subnormals, that is absolutely the cause of this kind of performance. So indications are that the subnormal problem was actually a much much bigger issue round the turn of the century and the birth of x86_64, that microarchitectures of that era genuinely forewent hardware subnormal handling that used to be provided and went for microcode instead.

The problem isn’t the penalty of floating point processing in the CPU. It’s that Windows configures the CPU to raise an exception every time a denorm is encountered, making the kernel fix up the denorm. This is why the penalty is absolutely crippling. Just a small sprinkling of denorms in a DAW would grind the computer to a halt when this happened on P4. The difference between P4 and everything before and after is that there isn’t actually a spec when the exception must or cannot be used. Intel simply decided that raising it at 2 orders of magnitude larger numbers was perfectly fine, and if the denorm handler has to spin its wheels and do nothing most of the time, it’s not their problem.

I highly recommend checking out section 3 of the 2006 paper “Quantifying the Interference Caused by Subnormal Floating-Point Values” by Isaac Dooley and Laxmikant Kale, it’s a citation from the Wikipedia article on subnormal numbers (under “performance issues”). They have a chart of subnormal operation slowdown rates across various then-contemporary architectures, and there’s a strong relation with pipeline complexity.

This is an issue of expectations. Floating point math was never intended to be used where exactness is required! It’s meant for dealing with inexact empirical values where the rounding error in floating point math will be completely swamped by measurement error. Unfortunately, because many programming languages completely lack exact rational types (and even worse, some don’t even have integer types!) a lot of programmers got the mistaken impression “float is for anything that’s not an integer”. This can cause big problems when you use floating point for operations that must be exact or must always be rounded a certain repeatable way (like finances).

in more complex cases, typically you would use arbitrary-precision arithmetic: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arbitrary-precision_arithmetic This is slower and more memory-intensive than floating point, but is also far more accurate.

Terrible sounding audio fades in “perfect” 16 bit digital systems alerted to the horrible reality that 16 bits is not nearly enough to fool human ears into accepting brittle-bright digitialia as analog warmth. Their solution was to add noise…and more bits. SOUND QUALITY site sent me here.

I designed the floating point execution unit used in the 387, 80960, and 486. This is a good discussion of the limitations of a digital number representing irrational numbers. Prof. Kahan developed the IEEE standard which was implemented first in the 8087. I became well versed in how to handle Guard, Round, and Sticky bits for rounding of numbers. The issue of a “subnormal”, more commonly known as a denormal number is a number that is smaller than the most negative exponent will allow such that the mantissa has leading zeros. I have no idea why Broadwell would require 123 clocks for normalization but I can tell you that as of the 486 and Pentium Pro/II/III generations denormals used 4 or 8 bit shifts. This led to a maximum of 3-6 clocks for single precision denorms. The largest penalty was for Extended Floating point, which is really never used as it is even larger than double precision. The option of “flush to zero” has been around for a while and there is periodically a lively discussion about whether to use denormals or just flush to zero.

Transcript

Click to reveal

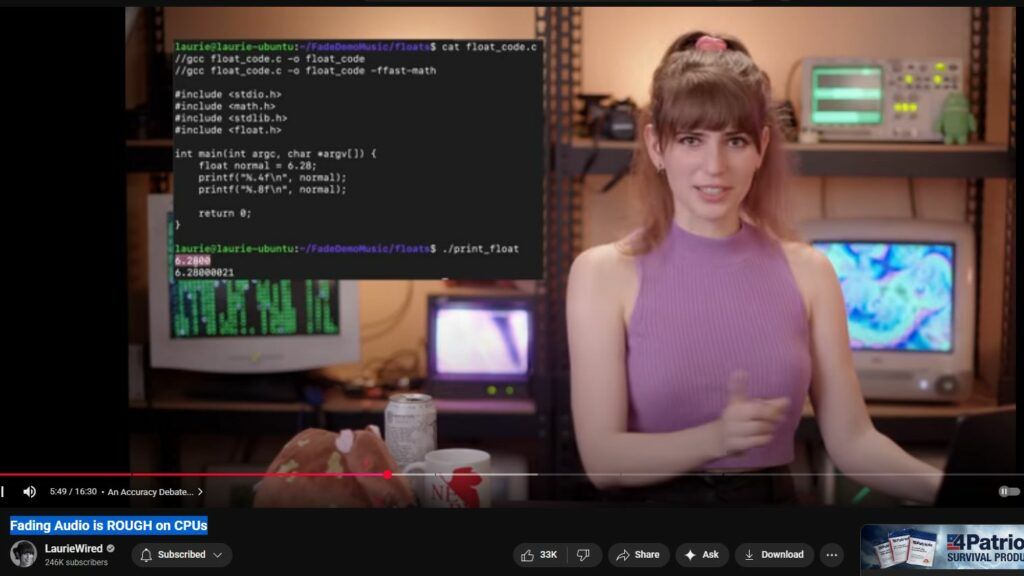

Fading Audio is ROUGH on CPUs (LaurieWired)

Here’s a summary of the key insights from the video “Fading Audio is ROUGH on CPUs” by LaurieWired:

Why Audio Fades Can Be Surprisingly Demanding on CPUs

- Subnormals and Floating-Point Performance

When an audio signal fades out, its volume is reduced gradually toward zero. As the numbers get extremely small—entering the range of subnormal numbers—floating-point units on CPUs require disproportionately more clock cycles to process them accurately (PC Gamer). - Historical Impact on Older CPUs

This wasn’t just a corner case—especially older processors like Intel Pentium 4 struggled significantly when processing these subnormal values, sometimes grinding computation to a halt (PC Gamer).

How the Video Breaks It Down (Timestamp Highlights)

The video walks through various layers of the problem, including:

- Subnormal Arithmetic Cost (00:00)

- An Accuracy Debate… (02:25)

- Too Small to Calculate? (06:28)

- IEEE 754 (Floating‑Point Standard) (08:56)

- Digital Audio Workstation (DAW) Conundrum (10:17)

- A Massive CPU Spike (14:18)

(YouTube, Sonic State)

Modern Solutions to the Problem

- Avoiding the Cost of Subnormals in DAWs

Today’s DAWs and modern processors (both x86 and ARM architectures) actively mitigate these problems. They do this by disabling subnormal handling when unnecessary or using special instructions that make processing these tiny values more efficient, thus preventing CPU overhead for inaudible audio detail (PC Gamer).

Additional Context from the Web

- PC Gamer’s Take

A lighthearted article emphasizes how something as seemingly trivial as a fade can become “one of the most CPU-intensive tasks you can possibly do,” underscoring how subnormal numbers can significantly tax CPU performance (PC Gamer). - LaurieWired’s Background

LaurieWired, debuting on YouTube only about two weeks before (back in mid-August 2025), has quickly gained attention for her clear explanations and technical explorations, including this standout video with over 350K views (YouTube).

Quick Recap

| Concept | Summary |

|---|---|

| Subnormals | Tiny floating-point values near zero that are resource-intensive to compute. |

| CPU Impact | Processing fades triggers many subnormals, spiking CPU usage, especially on older machines. |

| Modern Workarounds | DAWs and CPUs now often disable or optimize subnormal handling to conserve performance. |