Anti Musical Foiblishness Being real When 50 bars of Drum Solo is 52 bars too many

Steve Gadd: Signed, Sealed Delivered – Switzerland – 1989

I’m not “picking on” or singling out Steve Gadd; there are countless examples. Gadd and many other soloists are professional masters beyond reproach. I expect nearly no one will agree with if even understand the point I’m addressing — but I think screaming is not singing, and most drum solos are akin to screaming.

From the comments —

“IMO, there should Never be “drum solos” any more than there should be “clapping solos” or “foot [stomping] solos” (excepting purpose-specifics such as tap dancing, Riverdance, etc). They nearly Never sound truly good and almost Always (especially lately) devolve into slamming sped-up madness that is not too far from wild banging or tripled-up pattern repeats, sometimes in-time. Just my 2c after many years. Tasteful, reserved “solouhettes“, sprinkled throughout the musical jam, with tricky little tweaks and twerks adding kink within the moving, grooving structure — those are much more musical and palatable, IMHO. Songs are on the whole remembered for their emotive groove, the synergistic gathering of souls — players and enjoyers — all vibing with small point/counterpoint phrases and retorts, and almost never for any one-off show-off or runaway. Think about it. ChatGPT’s most recent “10 most famous drum solos” is Weckl in 1992. That pretty much tells the unspoken truth, no?”

The dead giveaway of “way too much” is usually the full-wrist twist accompanying the full-elbow pivot and seeing and hearing when even That isn’t nearly enough — in fact, it seems literally kicking a hole through the bass drum or sledge hammering the shells themselves though the stage and into concrete bedding would not be enough. (Isn’t there some film in which Keith Moon kicks over his drumset or something like that? Drug-addled, wild cavalier abandon and disregard from unfocused, misplaced intensity (?)– reminds of the farcical “Animal” muppet, in the trashcan presumably with good reason.) IMHO, that is when all dynamic interest, value and prowess vanishes; all couth evaporates (and ‘foaming at the mouth’ likely ensues); the always-vaunted “quiet intensity” embarassingly (yes) immolates; and those sticks-transformed-into-wooden-bats suddenly become majorette batons, sometimes “topped” further by finger-spinning, knuckle-twirling, air-tossing — honestly I’m surprised no one has yet ignited the ends on-fire! I’m half-expecting to see LED-embedded flishy-flashy drumsticks before too much longer – and maybe with some tattoos and piercings on the sticks themselves! Makes me think of insanely chewing off the reed end of a sax for added “bite”, or blowing an industrial air compressor through a trumpet, or death-grinding/yaw-curling a bow into a violin neck until smoke then conflagration, or hammer-clawing steel strings off a guitar fretboard, or elbow-hammering a piano until handfuls of the keys detach, splay and haphazardly fly off this way and about. Or, otherwise generally approaching such anti-musical calamity. Why not “play” with literal sledge-hammers? Yeah, I’m pretty sternly against most “drum solos”; there is good reason “ffff” is the 11-out-of-10 with no 12 possible…more (of what should be) an unattainable limit than actual accomplishment.

In at least one interview I’ve seen, Buddy Rich himself almost related the ‘carnival barker’ batonish showmanship of drum solos (seemingly eschewing the solo whilst concommitantly embracing if not glorifying it). As musicality devolves, let’s call out nearly all drum solos for basically what they nearly all are: noisy shite. There is inglorious reason the drum-solo-only ‘bucket drumming’ is always an aside, never a stage-placed band-mate, forever a sidewalked exception, something to briefly tolerate, then walk brisky by and escape.

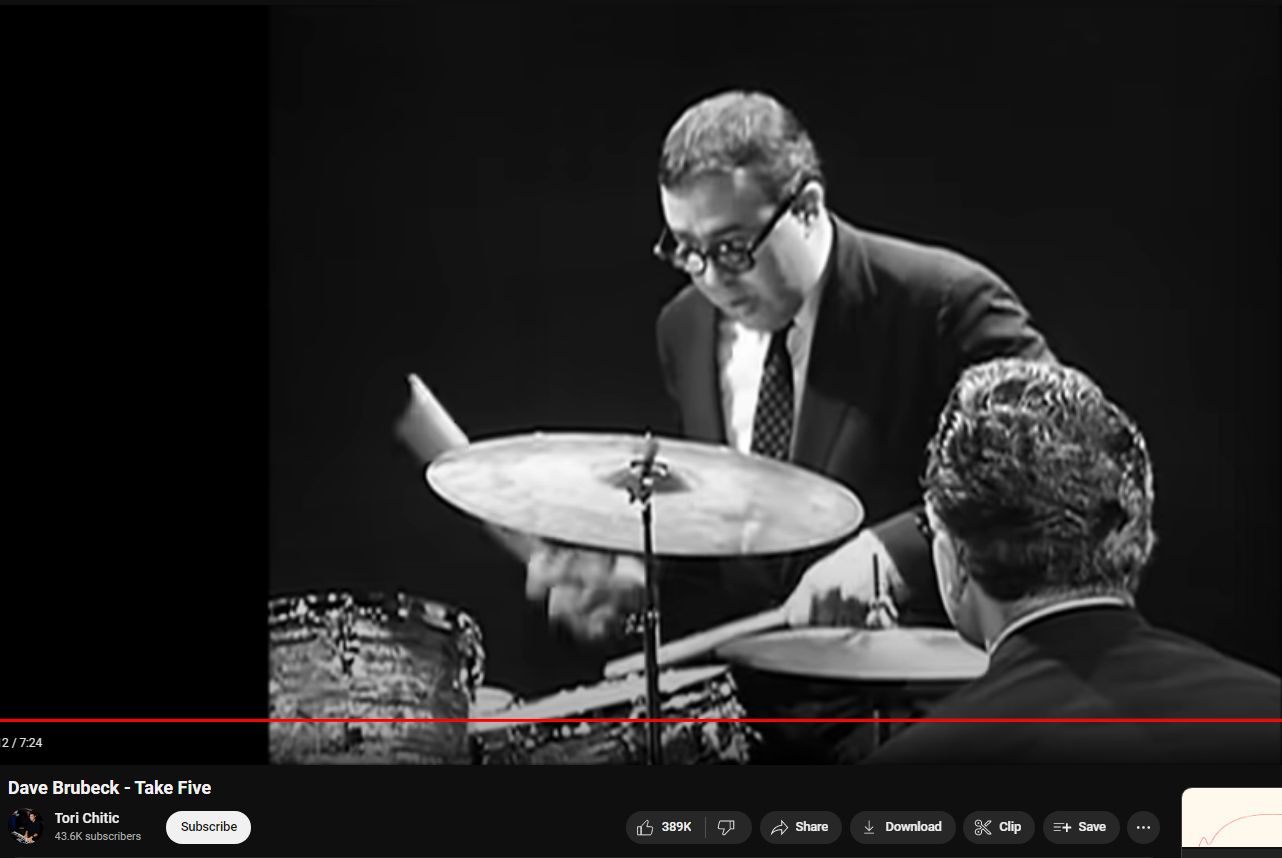

One of the Precious Few enjoyable exceptions, again IMHO, is the tasty getaway in Take Five by Joe Morello — https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tT9Eh8wNMkw (Notice how Morello’s power remains in the focused intensity of his playing; physically, his forearms almost never exceed parallel position to the floor! Nearly all subsequent drum solos exhibit pitiously tasteless runaway behavior, IMHO, a dramatic departure from musicality, as if mouth-agape chicken-flapping elbows add anything but ruffled spectacle. Also, curiously (tellingly?) (though it may be due simply to an artifact of the technology), if you examine the motion-blur, Morello’s is almost always blurred in his upstrokes, pulling Away from the drums! His drumward attacks are so absolutely fast, seemingly, that they escape blur altogether, like incoming Bruce Lee punches might exceed perception. As we know from armament ballistics, the power of force is developed by projectile speed rather than increased mass.

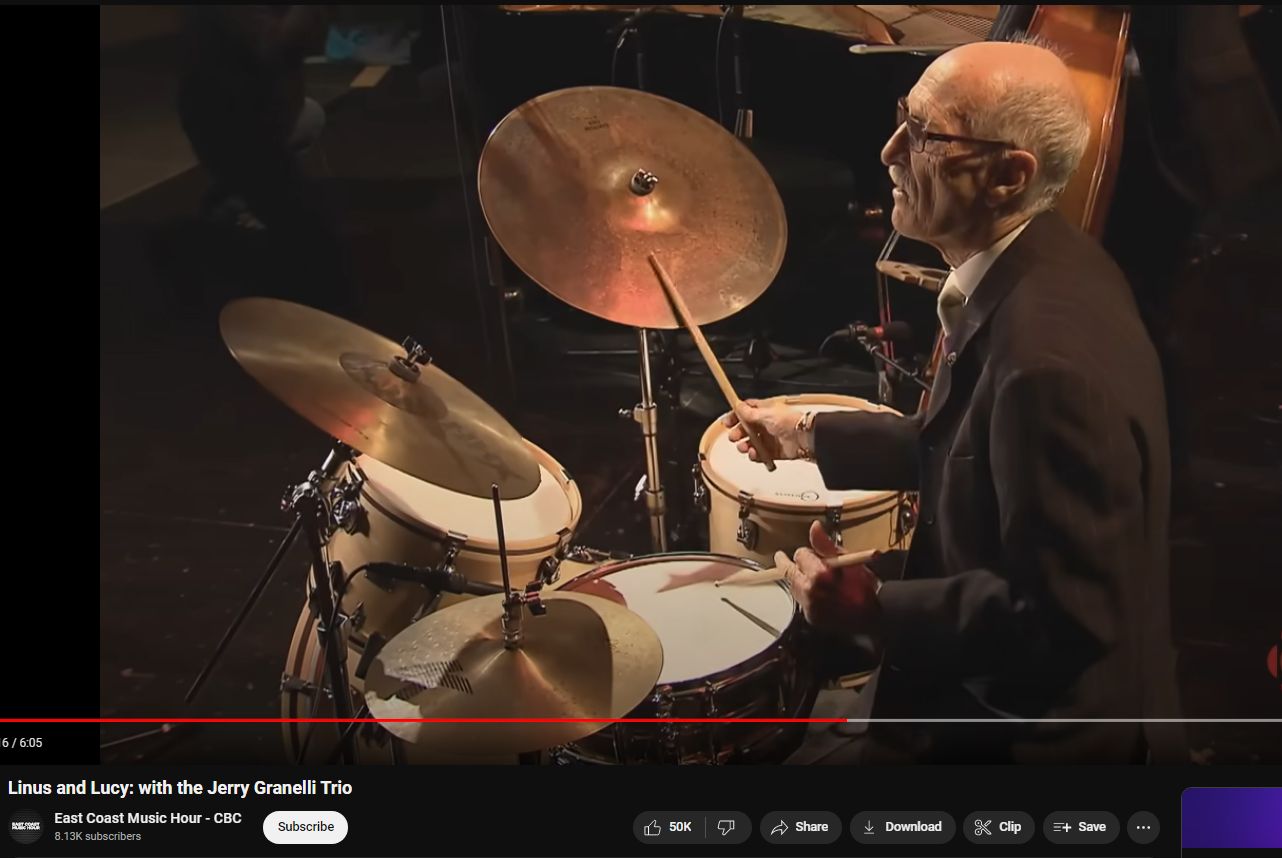

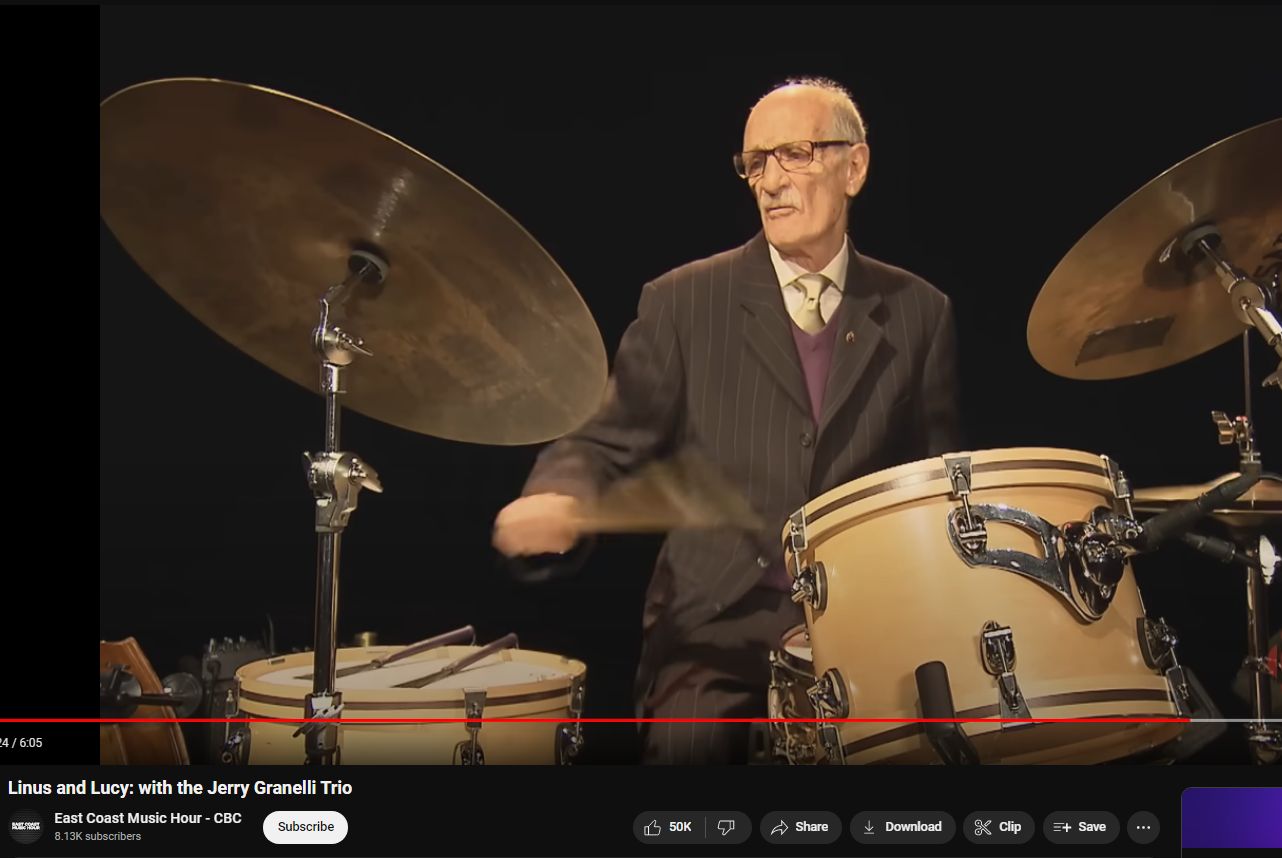

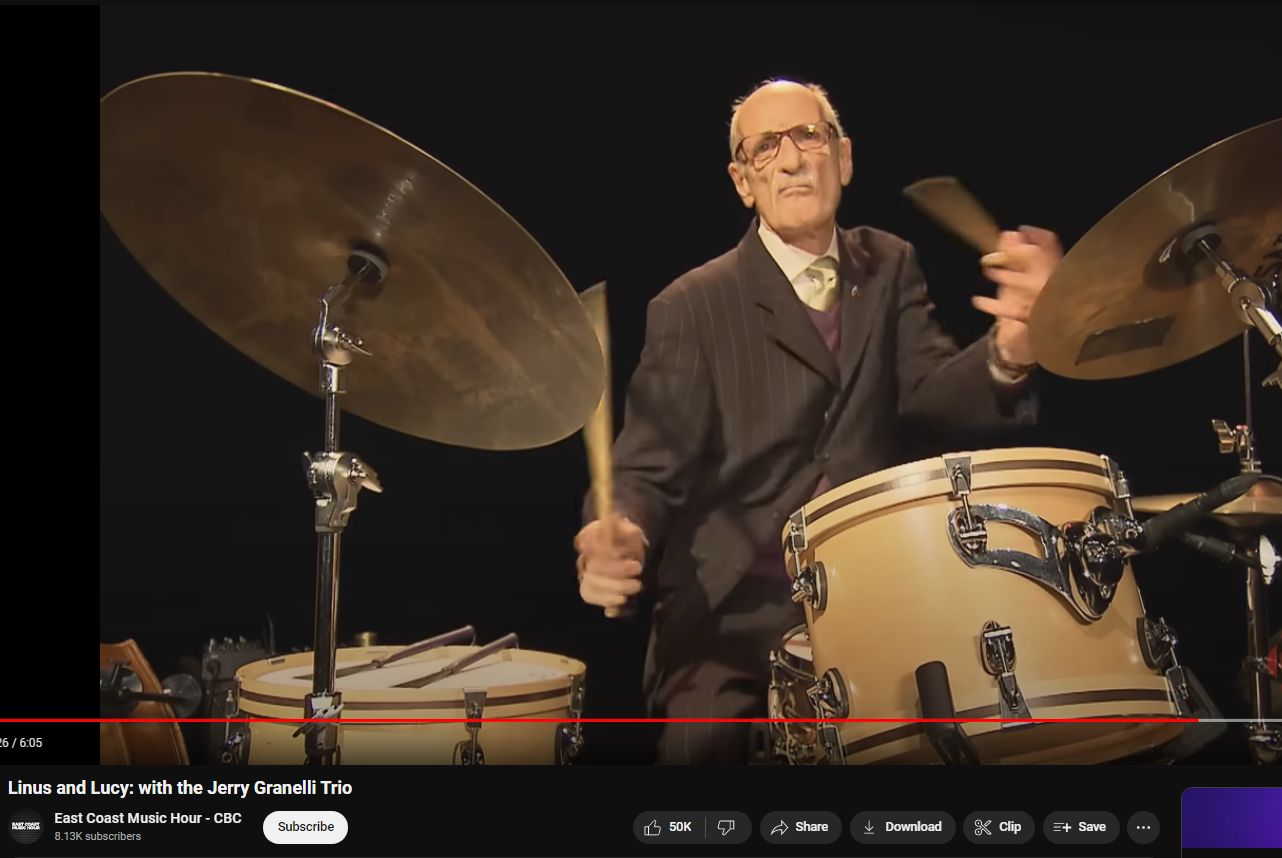

Another delicioso of quiet intensity and focused restraint is here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OODA_K5hxyc — with any “solo” being kept to accented notes or sub-bar phrases. The music is helped not assailed.

Note similarly that Granelli’s forearms never exceed parallel position to the floor, even under his max power in this epically musical performance. The power and emotive feeling is Not in any power swings but instead the maintained, controlled focused intensity. This actually entails less motion of mass; it is the opposite of most power-slam drum solo exhibitions.

Examining Granelli’s sparse “forte” notes in this tune. From the comments: “This is the musical equivalent of a bar of pure gold.”

I wager that full-swing drum solo strikes in fact tally worse (meaning less groovy, less musical) in every drum metric — head and/or cymbal displacement and distortion, overtone smearing, leading/cutting edge time elongation (the measurable, visible and audible tilting/extension of the theoretically infinitely-fast “step function” from zero-to-one that is the leading edge “attack” of all strikes or staccato notes) — bashing stretches the impulse out over time, actually reducing its instantaneous power and “cut”. Again, that’s my opinion, I haven’t measured it yet: I predict the bashing strikes will in fact exhibit measurably slower waveform rise-times with smeared fidelity, indicating general agreement between measurement and (some listener) subjectivity that ‘slams sound worse’.

Here’s another example of msuical dynamic power sans batter-swing — https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q-zXBHwEcC4

Krupa exhibits similarities — https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fyAUKU_ImNg — I don’t think these are coincidental.

Even the wonderful Gregg Bissonette generates power without much motion, keeping dynamics, maintaining that controlled / “quiet” intensity — https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UwWcMAxOLPk — power floor-tom strokes at around 16:40 in

Take Five

The drum solo in “Take Five” is one of the most iconic and recognizable drum solos in jazz history, performed by drummer Joe Morello as part of the Dave Brubeck Quartet’s rendition of the song. Here’s an analysis of Joe Morello’s drum solo in “Take Five”:

1. Timing and Meter: “Take Five” is played in 5/4 time signature, which gives it a distinctive and unconventional feel compared to standard jazz compositions. Joe Morello’s drum solo explores the rhythmic possibilities of this time signature, showcasing his mastery of odd meters.

2. Melodic Elements: Morello incorporates melodic elements into his drum solo, using the drums as melodic instruments in addition to providing rhythmic support. This is particularly evident in his use of the ride cymbal bell and tom-toms to create melodic phrases.

3. Dynamic Control: Morello demonstrates exceptional dynamic control throughout the drum solo, varying the volume and intensity of his playing to create contrast and emphasize different rhythmic patterns.

4. Polyrhythms and Syncopation: The drum solo in “Take Five” features intricate polyrhythms and syncopated rhythms, with Morello layering multiple rhythmic patterns simultaneously. This complexity adds depth and texture to the solo, showcasing his technical proficiency and musical creativity.

5. Use of Space: Morello’s drum solo in “Take Five” also highlights his use of space and silence as musical elements. He strategically incorporates pauses and rests, creating moments of anticipation and tension before launching into new rhythmic patterns.

6. Innovative Techniques: Throughout the solo, Morello employs innovative drumming techniques, such as stick control, ghost notes, rim shots, and cross-sticking, expanding the sonic possibilities of the drum set and pushing the boundaries of jazz drumming.

Overall, Joe Morello’s drum solo in “Take Five” is a masterclass in jazz drumming, combining technical precision, musicality, and creativity. It remains a timeless example of how a drummer can elevate a song through inventive and expressive drumming techniques.

10 Most Famous Drum Solo Performances

Here are ten of the most famous drum solo performances in music history, showcasing the skill, creativity, and innovation of legendary drummers across various genres:

1. Gene Krupa – “Sing, Sing, Sing” (1937): Gene Krupa’s iconic drum solo in Benny Goodman’s recording of “Sing, Sing, Sing” is considered one of the most influential drum solos in jazz history, showcasing his dynamic playing style and technical prowess.

2. Buddy Rich – “West Side Story Medley” (1968): Buddy Rich’s virtuosic drum solo in the “West Side Story Medley” demonstrates his incredible speed, precision, and musicality, solidifying his reputation as one of the greatest drummers of all time.

3. John Bonham – “Moby Dick” (1970): John Bonham’s legendary drum solo in Led Zeppelin’s “Moby Dick” showcases his powerful drumming style, use of dynamics, and improvisational skills, earning him recognition as a rock drumming icon.

4. Keith Moon – “My Generation” (1967): Keith Moon’s explosive drum solo during The Who’s live performances of “My Generation” exemplifies his chaotic yet innovative approach to drumming, incorporating rapid fills and energetic beats.

5. Neil Peart – “The Rhythm Method” (1981): Neil Peart’s drum solo in Rush’s live performances of “The Rhythm Method” features complex rhythms, intricate patterns, and impressive use of percussion instruments, highlighting his technical mastery and creativity.

6. Billy Cobham – “Stratus” (1973): Billy Cobham’s drum solo in “Stratus” from his album “Spectrum” showcases his fusion of jazz, rock, and funk styles, with intricate patterns, polyrhythms, and dynamic changes.

7. Terry Bozzio – “The Black Page Drum Solo” (1976): Terry Bozzio’s performance of Frank Zappa’s “The Black Page Drum Solo” is renowned for its complexity, incorporating intricate patterns, odd time signatures, and melodic elements on a large drum kit.

8. Dave Weckl – “Garden Wall” (1992): Dave Weckl’s drum solo in “Garden Wall” from his album “Heads Up” demonstrates his technical precision, fluidity, and ability to seamlessly blend jazz, fusion, and Latin rhythms.

9. Tony Williams – “To Wisdom the Prize” (1969): Tony Williams’ drum solo in “To Wisdom the Prize” from Miles Davis’ album “Miles in the Sky” showcases his innovative approach to jazz drumming, with lightning-fast fills, syncopated grooves, and dynamic shifts.

10. Ginger Baker – “Toad” (1966): Ginger Baker’s drum solo in Cream’s “Toad” highlights his unique jazz-influenced drumming style, incorporating polyrhythms, improvisation, and use of mallets and cymbals.

These drum solos represent a range of styles and techniques, each leaving a lasting impact on drumming and music history while showcasing the artistry and skill of the drummers who performed them.

Around 53:00 in is yet another Great example of why to Not do a drum solo. Extremely unmusical. Furious pounding. Reminds of ‘show lifting’ at a gym: throwing weights around, callous, graceless, something like cutting heavy steel with too small a torch: just no way to do it rightly. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pp862e4vaug